What does it mean to call something strange? Or as ecological philosopher Timothy Morton (2016) frames it: how can anything not seem strange in a world that has been fundamentally altered at its core by the visible and invisible layers of human histories and human impact. If what we see is mere appearance and what is, is only partly apparent, then everything is very strange even when it doesn’t appear to be.

Our world has been queered. Has in fact always been queer.

For Morton, the strange, the queer, the weird, present a kind of logic that balances knowing and not knowing, a new way of thinking that is fitting for this world we find ourselves in.

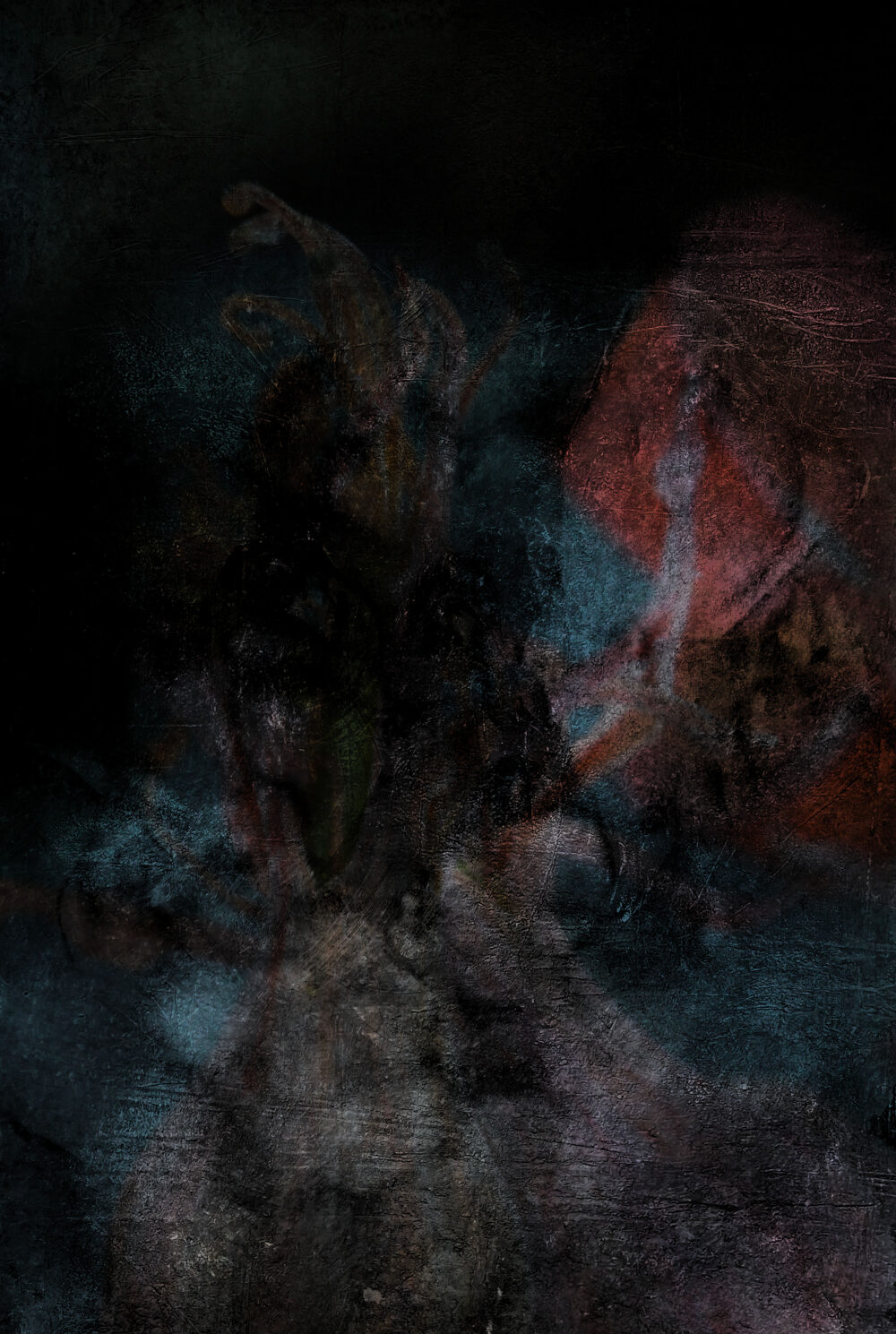

In two recent bodies of work I explore what Morton calls the “strange strangeness” of perception in the age of the Anthropocene. The layered, saturated imagery of this work evokes a sense of the ‘dark-uncanny’ which Morton postulates is a phase of ‘dark ecology’ as we pass from ‘dark-depressed’ to a ‘dark-sweet’ more hopeful perspective.

A strange appearance – variations, a series of 25 variations of one image exhibited with fellow Baldessin Studio printmakers in, In the Space of Elsewhere, is part of my ongoing engagement with abstracted variations on landscape and still life traditions. In playing with these forms I seek to investigate our troublesome representation of ‘nature’: all at once beautiful, monstrous and mysterious.

Designed to evoke a sense of both outer and inner space, these images begin with close-focused photography of foliage, flowers and other elements of urban gardens. They are built up through digitally layering multiple images over painted textures from abstract cold wax paintings which in turn have been the result of obsessive layering. This play with digital and painterly aesthetics, and with the recomposed image, have been a continuous part of my practice. The process of construction and deconstruction inherent in this approach to image makes explicit the persistent trace of the human hand in the ‘natural’ in our precarious times.

A strange appearance – variations takes one photogravure key plate developed through these techniques and then underlays a selection of different pigment prints to create variants which change in colour and form as the two layers intersect. This play with multiple variations speaks to both possibility and mutation: the open and the determined aspects of change.

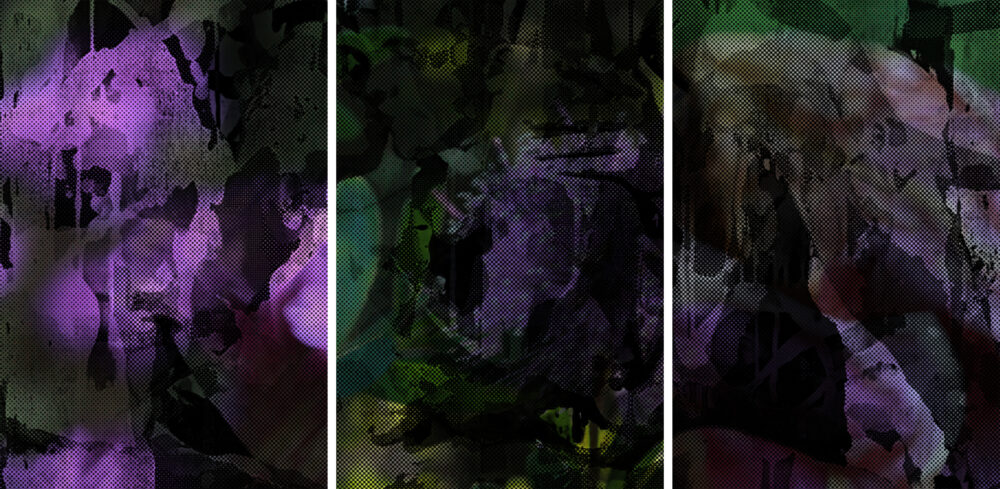

The second body of work, These two shapes together clinging, presented as part of the Midsuma exhibition Emerge O ut, also shows variations of an image: three variations of a triptych taken through different print processes.

The title references David Hockney’s seminal 1961 painting ‘We Two Boys Together, Clinging,’ a title he took from a Walt Whitman poem. Hockney’s early work was a brave public statement of queer desire at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in the UK. The underlying digital image in my piece takes a screen shot from gay porn and abstracts it through various digital processes, parts of the original imagery are still recognisable other elements merely maintain the register of the body. The queer body today still moves in and out of visibility.

The work combines various manual and digital print processes. The first version was exhibited last year as part of a group show of mokulito (wood lithography) work. Since then I have continued to experiment with this imagery through multiple print processes. In the original version the ‘key plate’ pigment print is overlayed by a coupling of biomorphic mokulito shapes. In the second version the original digital key plates have become photogravure plates and are overlayed onto colour pigment prints. In a third version the multiple levels of layering is done digitally and produced as a pigment print. In each version different elements of the underlying imagery are highlighted or hidden.

Shape and layer are both fundamental to the vocabulary of any image. But more than just structuring balance and depth, I take them to also be ways of knowing that connect us with bodies and histories and the strangeness of our times.

Layers reveal and conceal. The strange appearance of the Anthropocene is revealed/hidden in layers. When scientists want to confirm the emergence of a new geological era they look to evidence in the layered histories of ice cores drilled in Antarctica, or the the layers of sediment built up at the bottom of lakes. They can, for example, detect the sudden appearance of new elements such as plutonium that has fallen from the air and settled as a layer marking the beginning of the human made atomic era; or the sudden emergence in these cores of a human processed metal like aluminium.

While highlighting layers links to a type of archeological thinking, highlighting a sense of shape builds connections between our bodily shapes and the shapes around us, particularly the raw vegetal shapes of plant life. These vegetal or biomorphic shapes are both crafted and emergent in these two groups of prints. Jane Bennett suggests that this ‘mode of communication that proceeds via shape’ connects us to not only new ways of seeing but also new ways of being. Once attuned to these affiliative sensory connections “you become alert to them, and then there’s a slight but real kaleidoscopic shift in everything you see, hear, smell, touch, taste, and think. What becomes a little more sensible, conceivable, and plausible is the existence of a web of cross-body, shapely communications that subvents or is only vaguely hooked into more word-reliant networks. One may start to experience oneself less as an intersubjective being and more as an inter- and intra- twined shape.” (Bennett 2017: 103)

Bennett, J., 2017. ‘Vegetal life and onto-sympathy’ in Keller, C. and Rubenstein, M.J. eds., Entangled worlds: Religion, science, and new materialisms. Fordham Univ Press. pp.89-110.

Morton, T., 2016. Dark ecology: For a logic of future coexistence. Columbia University Press.

In the Space of Elswehere, Marcus O’Donnell, Sophia Szilagyi, Angela Coombs Matthews, Sorcha Mackenzie & Silvi Glattauer, Sol Gallery Fitzroy, 7-18 February

Emerge O ut, Brunswick Street Gallery, 27 January – 11 February

Marcus O’Donnell February 2024